Download top and best high-quality free Halberd PNG Transparent Images backgrounds available in various sizes. To view the full PNG size resolution click on any of the below image thumbnail.

License Info: Creative Commons 4.0 BY-NC

During the 14th, 15th, and 16th centuries, the halberd became popular as a two-handed pole weapon. The term halberd is most likely derived from the Middle High German words halm (handle) and barte (battleaxe), combined to form helmbarte. Halberdiers were the soldiers who carried the weapon.

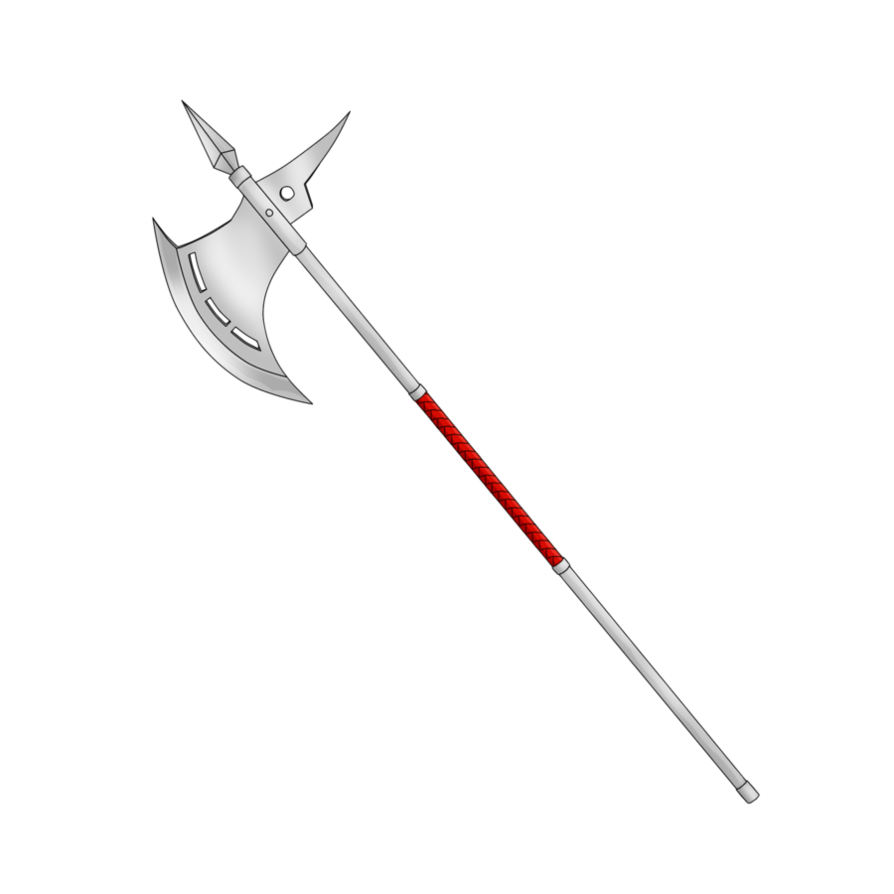

The halberd is made out of an axe blade with a spike on top that is fixed on a long shaft. For grappling mounted warriors, it always features a hook or thorn on the rear side of the axe blade. In terms of design and usage, it resembles some types of the voulge. The halberd’s length ranged from 1.5 to 1.8 metres (5 to 6 ft).

In Western Europe, the term has also been applied to a weapon from the Early Bronze Age. This was made out of a blade placed at a right angle on a pole.

The halberd was a low-cost weapon that could be used in a variety of combat situations. The tip of the halberd was improved throughout time to better cope with spears and pikes (and to allow it to drive back incoming riders), as was the hook opposite the axe head, which could be used to drag cavalry to the ground. A Swiss peasant killed Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, with a halberd, putting an end to the Burgundian Wars in a single blow. According to researchers, at the Battle of Bosworth, a halberd or a bill cut through the back of King Richard III’s head.

In the 14th and early 15th centuries, the halberd was the principal weapon of the early Swiss army. The pike was then introduced to help withstand knightly attacks and roll over opposing infantry formations. The halberd, hand-and-half sword, or the dagger known as the Schweizerdolch was employed for closer combat. The pike, reinforced by the halberd, was also employed by the German Landsknechte, who emulated Swiss fighting techniques, although their side arm of choice was a short sword known as the Katzbalger.

The halberd remained a useful supplemental weapon for pushing pikemen as long as they were fighting other pikemen, but as their position became more defensive, to protect the slow-loading arquebusiers and matchlock musketeers from sudden cavalry attacks, the percentage of halberdiers in pike units steadily decreased. By 1588, the Dutch infantry had been reduced to 39 percent arquebuses, 34 percent pikes, 13 percent muskets, 9 percent halberds, and 2% one-handed swords.

By 1600, infantry were no longer armed solely with swords, and sergeants were the only ones who used the halberd. The halberd was nevertheless employed sparingly as an infantry weapon far into the mid-17th century, albeit being rarer than it had been from the late 15th to mid 16th centuries. Halberdiers made up 7% of the infantry units in the Catholic League’s forces in 1625, while musketeers made up 58 percent and armoured pikemen made up 35 percent.

By 1627, the proportion of muskets, pikes, and halberds had shifted to 65 percent muskets, 20 percent pikes, and 15 percent halberds. At the Palace of the Marquises of Fronteira, a near-contemporary representation of the 1665 Battle of Montes Claros portrays a minority of Portuguese and Spanish soldiers with halberds. The troops in Antonio de Pereda’s 1635 painting El Socorro a Génova, which depicts the Relief of Genoa, are all equipped with halberds. German sergeants, who carried the halberd as a symbol of status, were the most constant users of the halberd throughout the Thirty Years War. They could use them in close combat, but they were most commonly employed to dress the ranks by gripping the shaft in both hands and thrusting it against numerous soldiers at once. They may also be employed to raise or lower pikes or muskets, preventing overexcited musketeers from shooting prematurely.

Download Halberd PNG images transparent gallery.

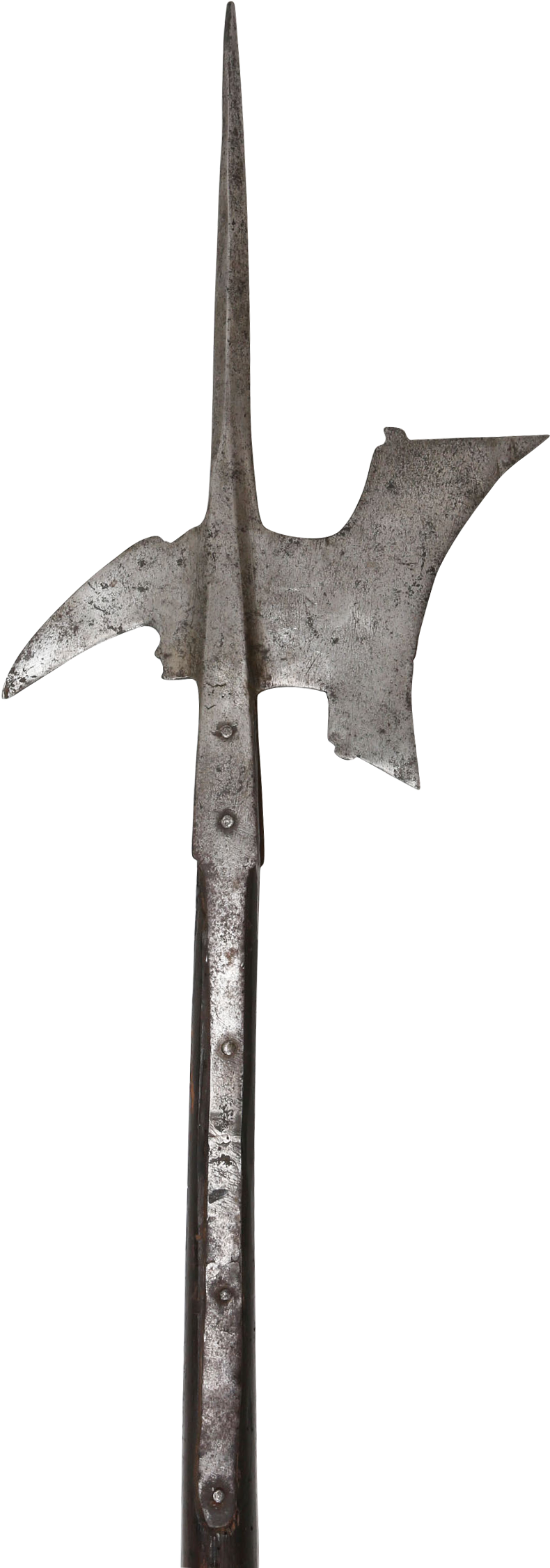

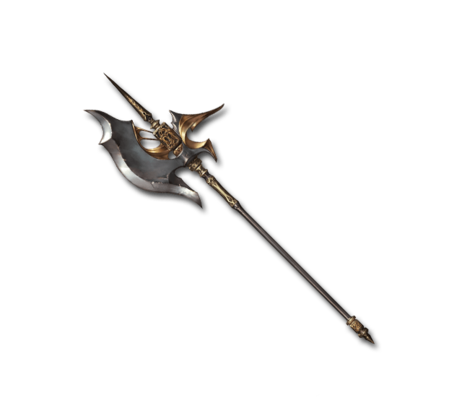

- Halberd No Background

Resolution: 1138 × 1482

Size: 291 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

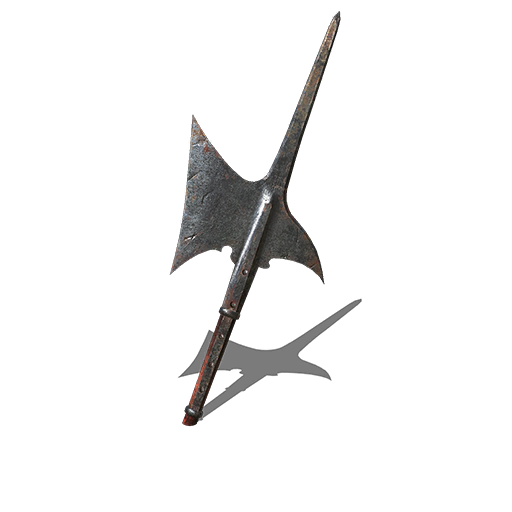

- Halberd PNG Images HD

Resolution: 545 × 512

Size: 41 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

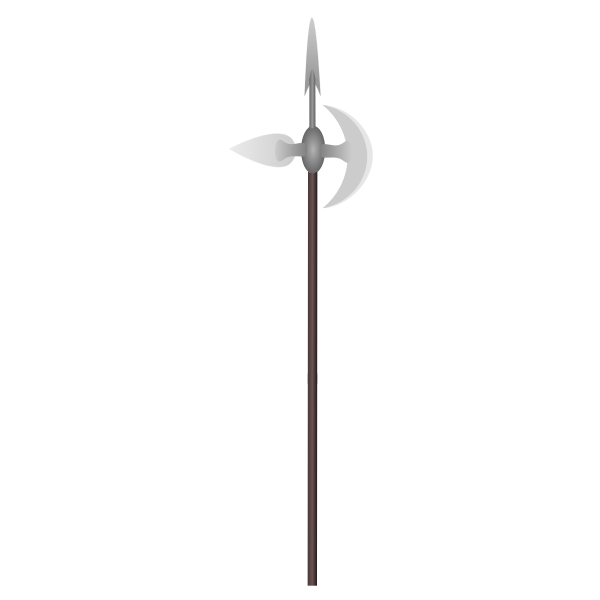

- Vector Halberd PNG Image HD

Resolution: 862 × 1001

Size: 112 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Free Image

Resolution: 819 × 819

Size: 51 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd No Background

Resolution: 1080 × 853

Size: 546 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Images HD

Resolution: 462 × 851

Size: 149 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Image File

Resolution: 734 × 843

Size: 167 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd Background PNG

Resolution: 633 × 885

Size: 70 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Free Image

Resolution: 2000 × 2200

Size: 367 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Background

Resolution: 790 × 2254

Size: 827 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG

Resolution: 600 × 600

Size: 13 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Pic

Resolution: 600 × 600

Size: 13 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG File

Resolution: 600 × 600

Size: 12 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Image

Resolution: 526 × 525

Size: 15 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Photo

Resolution: 462 × 400

Size: 38 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Cutout

Resolution: 512 × 512

Size: 57 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Images

Resolution: 1024 × 614

Size: 190 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Image File

Resolution: 512 × 512

Size: 15 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Photos

Resolution: 798 × 2329

Size: 177 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG

Resolution: 512 × 512

Size: 15 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Pic

Resolution: 512 × 512

Size: 28 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG File

Resolution: 512 × 512

Size: 16 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Image

Resolution: 512 × 512

Size: 14 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Photo

Resolution: 950 × 1280

Size: 230 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Cutout

Resolution: 651 × 326

Size: 10 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Images

Resolution: 512 × 512

Size: 12 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Photos

Resolution: 512 × 512

Size: 13 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd Transparent

Resolution: 640 × 565

Size: 71 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd Transparent

Resolution: 600 × 600

Size: 87 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Clipart

Resolution: 1206 × 1236

Size: 232 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG HD Image

Resolution: 630 × 315

Size: 92 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd

Resolution: 592 × 481

Size: 75 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Picture

Resolution: 928 × 1753

Size: 1227 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Halberd PNG Image HD

Resolution: 894 × 894

Size: 79 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd

Resolution: 900 × 941

Size: 117 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Clipart

Resolution: 1280 × 1280

Size: 112 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG Picture

Resolution: 798 × 587

Size: 47 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Vector Halberd PNG HD Image

Resolution: 1440 × 960

Size: 60 KB

Image Format: .png

Download