Download top and best high-quality free Mandarin PNG Transparent Images backgrounds available in various sizes. To view the full PNG size resolution click on any of the below image thumbnail.

License Info: Creative Commons 4.0 BY-NC

The word refers to officials selected under the imperial examination system; it includes and excludes eunuchs who are also active in the government of the aforementioned regions.

The phrase is derived from the Portuguese word mandarim (spelled in Old Portuguese as mandarin, pronounced ). In one of the first Portuguese accounts of China, letters from the imprisoned survivors of the Tomé Pires’ embassy, which were most likely written in 1524, and in Castanheda’s História do descobrimento e conquista da ndia pelos portugueses, the Portuguese phrase was employed (c. 1559). The name was also used by the Portuguese, according to Matteo Ricci, who reached mainland China from Portuguese Macau in 1583.

Many people assumed the Portuguese term was linked to mandador (“one who commands”) and mandar (“to command”), both of which come from the Latin word mandare. Modern dictionaries, on the other hand, believe that it was derived from the Malay menteri (in Jawi:,) which was derived from the Sanskrit mantri (Devanagari:, meaning counselor or minister – etymologically tied to mantra). According to Malaysian scholar Prof. Ungku Abdul Aziz, the term originated when Portuguese living in Malacca during the Malacca Sultanate wanted to meet with higher officials in China and used the term “menteri” with an added “n” to refer to higher officials due to their poor command of the language.

Before the name mandarin became widely used in European languages, the term Loutea (with different spelling variations) was frequently used in European travel accounts to refer to Chinese scholar-officials in the 16th century. It appears often in works such as Galeote Pereira’s description of his travels in China from 1548 to 1553, which was published in Europe in 1565, or Gaspar da Cruz’ Treatise of China (as Louthia) (1569). According to C. R. Boxer, the word derives from the Chinese (Mandarin Pinyin: loye; Amoy dialect: ló-tia; Quanzhou dialect: lu-tia), which was often used to address authorities in China. This is also the term used to refer to the scholar-officials in Juan González de Mendoza’s History of the Great and Mighty Kingdom of China and Its Situation (1585), which heavily drew (directly or indirectly) on Pereira’s report and Gaspar da Cruz’ book, and which was the Europeans’ standard reference on China in the late 16th century.

In the West, the name mandarin is connected with the notion of the scholar-official, who, in addition to fulfilling civil service tasks, immersed himself in poetry, literature, and Confucian studies.

European missionaries translated the Chinese moniker Guanhua (“the language of the officials”) for the Ming and Qing empires’ speech standard, which was already in use during the Ming dynasty, into “Mandarin language.” The name “Mandarin” also refers to the larger collection of Mandarin dialects prevalent across northern and southern China, as well as current Standard Chinese, which evolved from the previous standard.

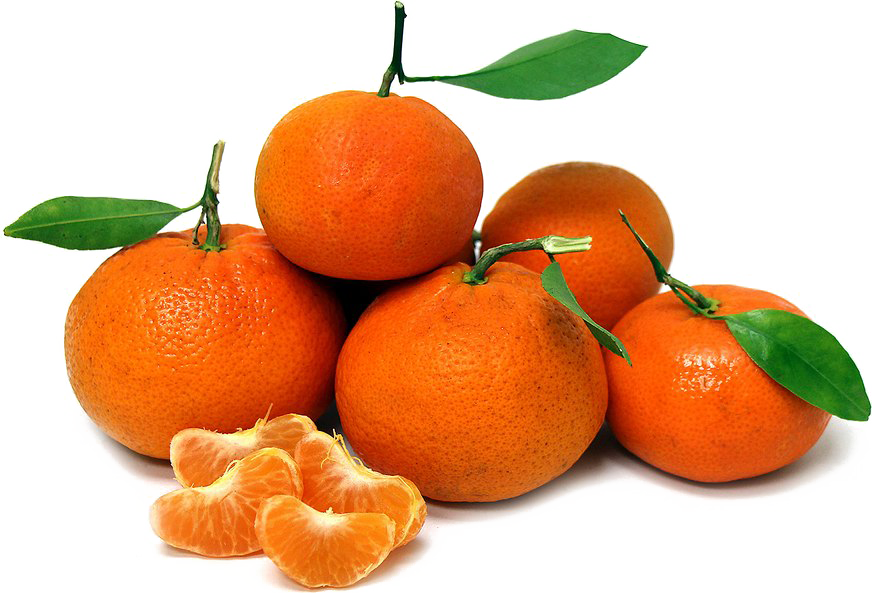

Download Mandarin PNG images transparent gallery.

- Mandarin PNG Image HD

Resolution: 500 × 500

Size: 56 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

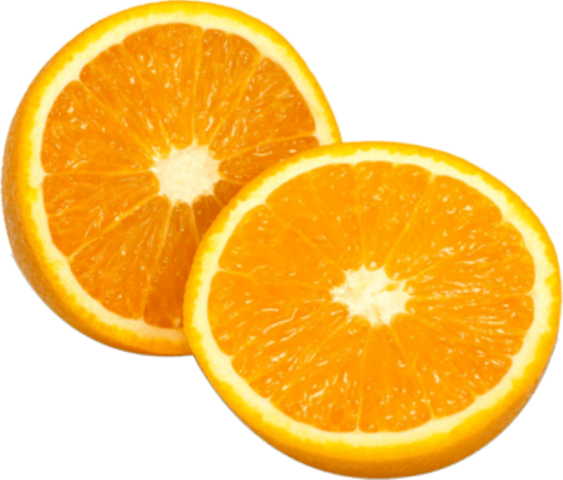

- Mandarin Orange PNG HD Image

Resolution: 825 × 650

Size: 185 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

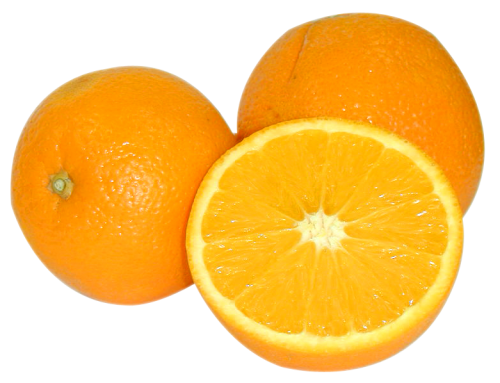

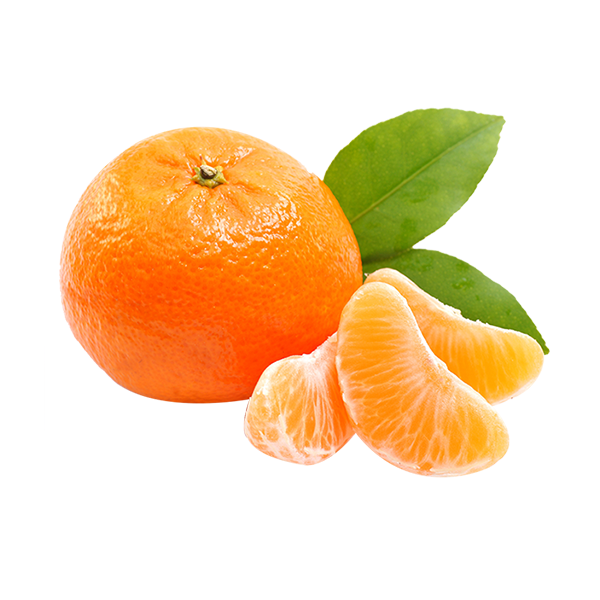

- Mandarin Orange PNG

Resolution: 1280 × 1280

Size: 914 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

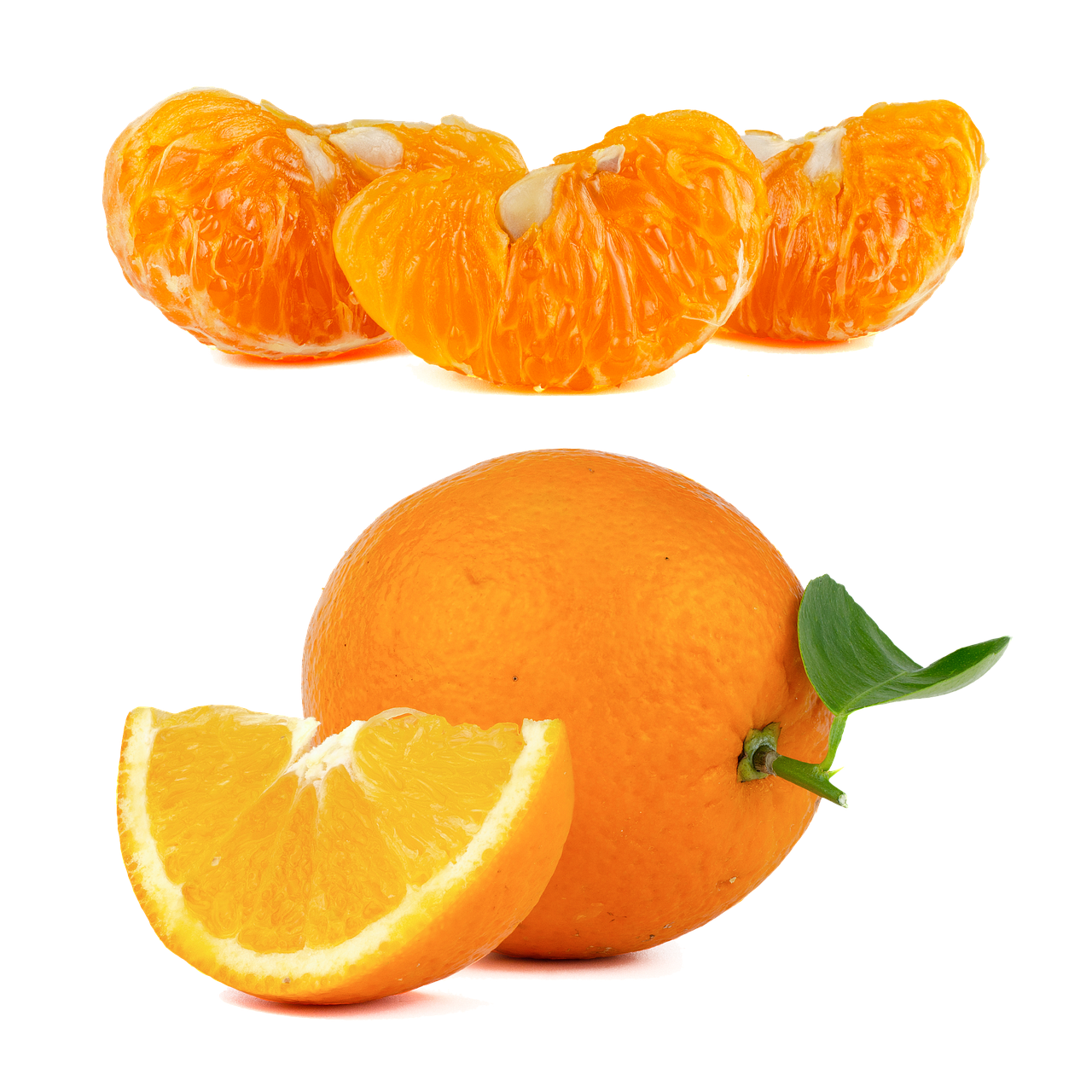

- Mandarin No Background

Resolution: 512 × 512

Size: 35 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange PNG Pic

Resolution: 563 × 480

Size: 111 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG Images HD

Resolution: 500 × 383

Size: 219 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange PNG File

Resolution: 886 × 886

Size: 536 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG Free Image

Resolution: 990 × 893

Size: 1167 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange PNG Image

Resolution: 1280 × 1280

Size: 1358 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG

Resolution: 700 × 584

Size: 145 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG Pic

Resolution: 700 × 492

Size: 270 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG File

Resolution: 1263 × 585

Size: 993 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG Image

Resolution: 1595 × 1166

Size: 2240 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG Photo

Resolution: 800 × 800

Size: 551 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG Cutout

Resolution: 980 × 471

Size: 536 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG Images

Resolution: 500 × 425

Size: 231 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG Photos

Resolution: 1500 × 1500

Size: 407 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin

Resolution: 3976 × 2652

Size: 4912 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange

Resolution: 640 × 414

Size: 223 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange PNG Photo

Resolution: 720 × 720

Size: 415 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Transparent

Resolution: 457 × 338

Size: 187 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG Clipart

Resolution: 501 × 331

Size: 263 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange PNG Cutout

Resolution: 470 × 350

Size: 113 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG Picture

Resolution: 1280 × 1181

Size: 808 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange PNG Images

Resolution: 872 × 593

Size: 575 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange PNG Photos

Resolution: 819 × 573

Size: 267 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange Transparent

Resolution: 850 × 839

Size: 670 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin PNG HD Image

Resolution: 536 × 595

Size: 334 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange PNG Clipart

Resolution: 600 × 600

Size: 295 KB

Image Format: .png

Download

- Mandarin Orange PNG Picture

Resolution: 650 × 651

Size: 142 KB

Image Format: .png

Download